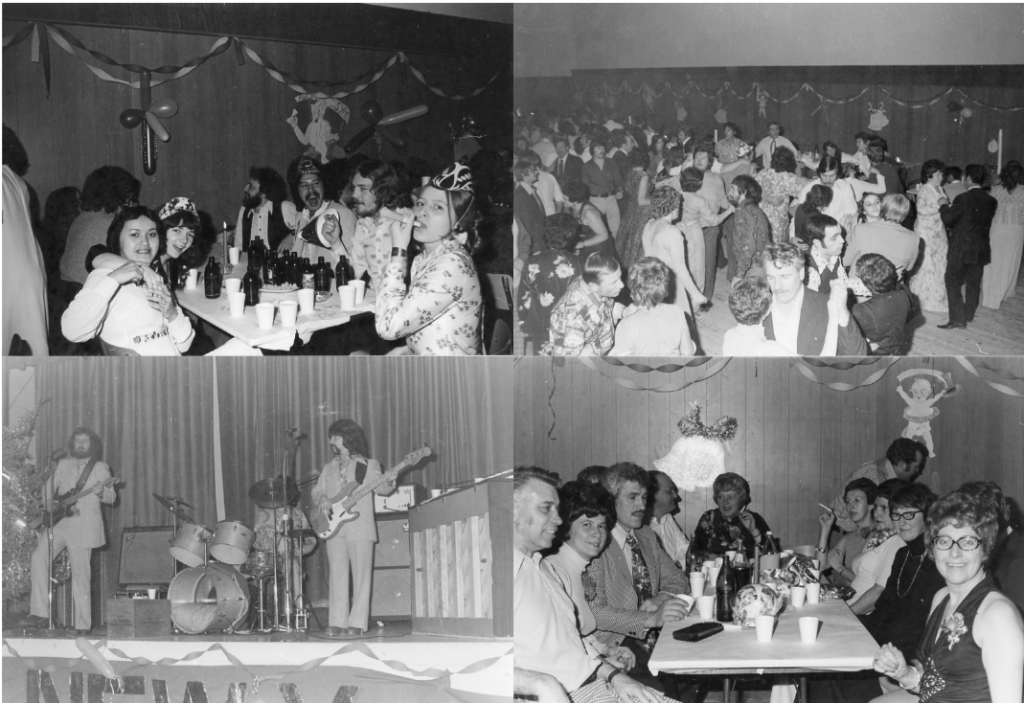

In mid-August of 2021, a nondescript cardboard box full of envelopes was donated to the Bulkley Valley Museum. Within each envelope were strips upon strips of black-and-white negatives depicting people, scenery, and events from Houston, B.C. This pictorial treasure trove was the work of photographer Bill Dungate, who with his camera and darkroom documented nearly 100 years of the town’s history. Beginning in the late 1960s, he was called upon to photograph weddings, dances, graduations, parades, craft sales, conventions, and many other community events. In addition to recording Houston’s present, he also preserved its past, reproducing and enhancing old photographs lent to him by friends, relatives, and neighbours. This work continued up until Bill’s death in 1993 at the age of 84.

The Bill Dungate collection fills an important gap in the Bulkley Valley Museum’s archives: up until this point we had very few photographs relating to Houston. Although our collections mandate focuses primarily on Smithers, we also accept material relating to other communities in the Bulkley Valley, particularly as Houston has no centralized archival repository of its own.

The arrival of this box marked the beginning of over a year of fascinating – and ongoing – archival work. In this blog post, we’ll go behind the scenes and explain how that work is carried out. First of all, though, let’s take a look at the man behind the camera – Bill Dungate himself.

Who was Bill Dungate?

Bill Dungate was well-suited to the role of Houston’s unofficial photographic historian, having spent almost an entire lifetime in the area. Born to George and Sicreal Dungate of Vernon, B.C., in 1909, he moved to Houston with his family at the age of five. His father had pre-empted land south of town the previous year. As a child, Bill was part of the first class at the original Houston School, established in 1916.

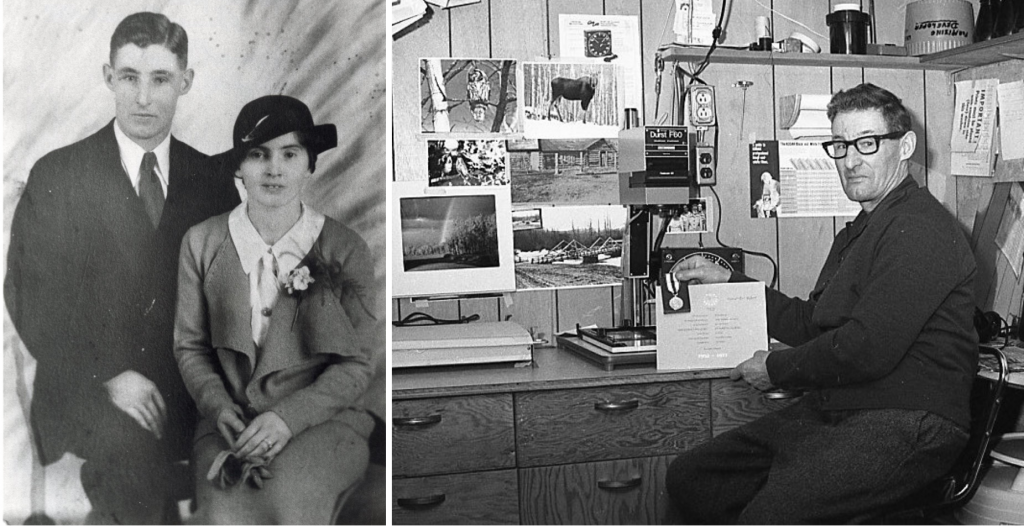

After about a decade of farming in the Houston area, the Dungate family moved to Prince Rupert in 1924. It was here that Bill married his childhood classmate, Betty Aitken, on November 11th 1935. Betty had been born in 1914 to Tom and Nora Aitken, farmers in the North Bulkley area; her aunt and uncle, Archibald and Jessie McInnes, owned Pioneer Ranch nearby. Bill and Betty moved back to Houston in 1943 with their young daughter, Nora (b. 1938).

The Dungates spent the rest of their lives in Houston and made many contributions to the community. In addition to his work as a photographer, Bill was a farmer, logger, conservationist, and weatherman for the Forest Service. Betty was instrumental in the development of the Houston Women’s Institute, and wrote the first history of Houston with her sister Nancy Goold in the 1950s. This document served as the foundation of the 1971 Houston history book, Marks on the Forest Floor, and its 1999 successor, Marks of a Century. Bill’s achievements were honoured with a Queen’s Jubilee Medal in 1978, and both he and Betty were declared Freemen of Houston in 1985. Bill and Betty passed away in 1993 and 2004 respectively.

Processing the Dungate Collection

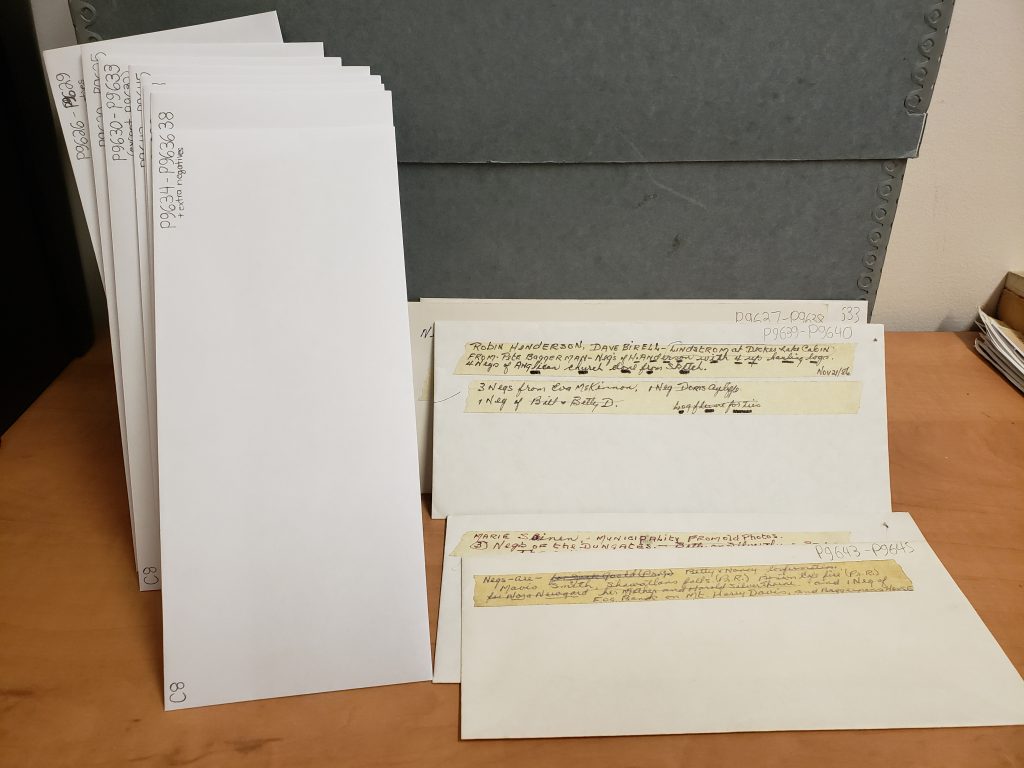

Upon its arrival at the Museum, the Dungate collection consisted of roughly 200 envelopes full of negatives, plus several boxes of printed photographs and 63 cases of slides – a rough estimate of 5,000 individual images in total. The process of sorting, identifying, digitizing, cataloguing, and rehousing this enormous amount of material has taken around 1,000 hours and counting. As of the time of writing this post, 475 photographs and negatives have been entered onto our online database – and we haven’t even started on the slides yet!

Due to the sheer size of the Dungate collection, it would be impractical for us to give each and every image its own database record. Instead, Museum staff must take a representative sample of these photographs to be posted in our online collections.

How do we decide which pictures make the cut? The image’s quality and uniqueness are taken into consideration: particularly faint or blurry scenes, as well as those that are identical or very similar to photos already in the Museum’s collection, are passed over. The most important factor, however, is whether or not the photo can be identified as a person, place, or event relevant to the Bulkley Valley.

For the more recent negatives in Dungate’s collection, dating mainly from the 1970s and 1980s, the procedure was fairly simple. Each envelope had been labelled with a date and subject line (ex. “Community Bazaar, November 1979”), and usually contained negatives of one or two community events. The contents of each envelope would be scanned and examined on the computer. A sample of the best shots – for instance, those showing identifiable people or buildings, or different views and angles of a scene – would be selected for cataloguing. Special priority was given to those pictures which appeared in the Houston Today, as the paper often identified their subjects and provided additional information. Out of an envelope containing, for example, 30 or 40 images of a wedding, craft sale, or dance, only 5 or so might be kept to serve as representatives of the event. The other scans – especially blurry, redundant, or contextless photos – would be deleted in order to save room on our servers. All the physical negatives, however, would be retained for safekeeping.

Assessing the reproductions of antique photographs was more difficult. Instead of being grouped by events or topics, these negatives were arranged based on the date Dungate had produced them. This meant that each envelope might contain negatives of photographs lent by several different people, depicting events and individuals from the early 1900s up until the 1950s. Furthermore, while these envelopes were labelled – usually with the name of the donor, the date the photos were reproduced, and a brief description of the contents – there was rarely any indication as to which negative corresponded to which descriptor. To illustrate how confusing this might be, imagine an envelope labelled, among other things, “wedding of Mr. & Mrs. Smith” and “Johnson family photo.” When you open the envelope, you realize that among the negatives there are three different wedding photos and five portraits of families! How to figure out which is which?

To get around these obstacles, we consulted sources such as books and newspapers. The Houston Today was somewhat useful, but as the only issues available on Newspapers.com are from the late 1960s onwards, it was often too recent to be relevant. Far more helpful were the aforementioned Houston history books, Marks on the Forest Floor and Marks of a Century. Many of Dungate’s photographs actually appear in these books, with captions and plenty of information on the people and places shown in them. This information could also be used to help identify other negatives. To go with the examples from the previous paragraph, learning that ‘Mr. and Mrs. Smith’ were married in 1940 might enable you to eliminate two negatives which were clearly taken in earlier decades. Likewise, if you know that the Johnsons had five sons and one daughter, you might be able to pinpoint which family photo is theirs. Nonetheless, in spite of all these aids, many of the negatives remained unidentified and, therefore, do not appear on our database.

Once all the chosen negatives had been scanned and the extras deleted, each image was assigned a four-digit identification number, uploaded to our database, and given a description noting its date, location, and subject matter. The Marks books and Houston Today were often consulted to provide additional information. Knowing the who, what, where, when, and why of a photo increases its relevance to the historical record. Continuing our fictional examples, the wedding photo of Mr. and Mrs. Smith gains more poignancy if you know that Mr. Smith died in the Second World War two years after it was taken. Learning of the Johnsons’ contributions to their community enriches our understanding of the family in the portrait. Information about the negatives themselves – such as when they were produced and who the original photographs belonged to – is also recorded in these entries. All the photos on our database are available for public viewing on our Collections Online portal.

After digitization and cataloguing, the final step in preserving the negatives is to transfer them from the yellowing, decades-old envelopes they arrived in and place them in acid-free, archival-safe envelopes. Each new envelope is marked with the identification numbers of the negatives it contains. For the most part, the negatives are grouped in the same order as they had been by Bill Dungate. This emphasis on maintaining original order is part of the concept of respect des fonds, a principal concerning the integrity and authenticity of archival materials.

Hopefully this blog post has provided an interesting glimpse into the sometimes frustrating, sometimes fascinating work of an archivist. We invite our readers – especially those familiar with Houston’s history – to take a look at the Bill Dungate photographs available in our online collections. If you recognize an unidentified person or place, please feel free to let us know by leaving a comment on the photo or sending us a message at info@bvmuseum.org!

Many thanks to the donor of the Bill Dungate collection for helping make this piece of history available.