The following story was written by Smithers historian Harry Kruisselbrink and is republished here with permission from the author.

The year 2020 is the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. The BC/Yukon Command of the Royal Canadian Legion has decided that this year it will “focus on the 75th Anniversary of Dutch Liberation.” One Smithers resident was directly involved in the liberation of Holland. That man is David George Havard.

Dave Havard was born in Comox, British Columbia on June 6, 1923. Shortly after his birth the family moved to Victoria where he was raised. His father had been a Sergeant Major in the Canadian Army Service Corps in World War I and was awarded a Meritorious Service Medal for his efforts. So, when World War II broke out, Dave followed his father’s footsteps. After graduating from high school, he joined the army in August 1942 at the age of 19. He was given the regimental number K66741 and trained as an artillery signaller.

In 1943, he was sent overseas to England. He was still in England when, on D-Day, he celebrated his 21st birthday. He was assigned to the 5th Canadian Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery and on July 7, 1944, found himself on the shores of Normandy. His regiment was sent to the embattled city of Caen. There it came under heavy shell and mortar fire. Caen had been relentlessly bombed by both sides and it had been reduced to a mass of rubble, quite an eye opener for a newcomer to battle. Dave noted that “we quickly became adept at digging slit trenches for protection, much faster than we had done it in practice in England.”

It was also here that he experienced an event that stayed with him for the rest of his life. He was riding in a Bren gun carrier in a convoy with infantry marching along side. He recognized Casey, one of the Black Watch infantrymen. Casey and Dave had become friends during basic training in Canada. They started happily yelling to each other back and forth when, suddenly, a shell dropped nearby and a piece of shrapnel from it hit Casey and killed him instantly – fully alive one second, dead the next! This hit Dave hard, “You know, when you’re young and immature, you think you’re invincible, as I did. And I suddenly became aware that I was no longer invincible. And that’s the rude awakening you get when you’re young, in the service”. It also got him wondering if his parents would ever have to face the loss of their only son.

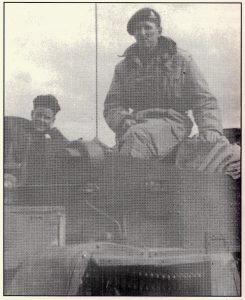

Dave spent most his time in the war in a Bren gun carrier. The carrier had a crew of four, the Forward Observation Officer (F.O.O.), an assistant F.O.O., a signaller and the carrier driver. From the carrier Dave transmitted the orders of the F.O.O. back to the artillery behind them. The F.O.O. directed the artillery fire so that it would most effectively hit the enemy. So Dave and his crew were always positioned ahead of the advancing troops and closer to the German lines. It was a dangerous position; F.O.O.s were specifically targeted by the Germans because of their crucial role in directing the artillery fire. It did have this going for it: most of the shells, from both the Allied and German side, passed by overhead.

The crew often went without sleep for up to 48 hours or so as the radio had to be on 24 hours a day 7 days a week.

On one occasion, the crew was parked on a road beside a hay field. Everything seemed peaceful and quiet and the crew had a chance to relax. Then the shelling started with air-bursting shells. It is possible, with a little luck, to dodge shrapnel from ground bursting shells by laying flat on the ground or in a trench but these were shells that burst overhead. Dave admitted, “I have never felt as vulnerable as I did with those overhead bursting shells”. At the same time machine gun fire was heading his way. “I made for the roadside ditch and as I crawled along it a hail of bullets ploughed the sidehill just above my head, showering me with mud.” Thankfully the infantry soon took out the machine gunner and the firing stopped. It was a traumatic experience and “I distinctly remember that it was one of the times I prayed.”

From Caen he was sent north and participated in the battle of the Scheldt Estuary in the area of the port city of Antwerp in northern Belgium and southwestern Holland. Although Antwerp itself had been liberated by the British, the entrance to the port, the Scheldt Estuary, some 50 miles (80 km) from the North Sea, was still in German hands. The Allies desperately needed the port to keep their supply lines operational so the Scheldt Estuary had to be cleared of the German occupiers.

The battle of the Scheldt Estuary proved to be very difficult, all the more so because of the waterlogged terrain. A number of Canadian regiments, including Dave’s were involved in this battle and they were also involved in the capture of Walcheren Island, a major German stronghold in the Dutch province of Zeeland. As Dave observed it was a “wet and flooded battleground” and it proved to be a formidable task.” From Walcheren, the Regiment moved inland and made good progress to Tilburg and then to Nijmegen.

The Regiment spent the harsh winter of 1944-45 in a small community called Malden in the Dutch Province of Gelderland. To provide shelter, they dug holes in the ground, covered them with materials they scrounged from the nearby deserted village of Groesbeek; boards, linoleum and even doors from houses that had been abandoned or destroyed by the owners as they fled for their lives during battle. They also found a source of heat from nearby coal and firewood. Light came from a generator powered by a derelict Jeep motor. All very primitive and not at all comfortable but it had to make do!

While there, Dave even learned a little bit of Dutch. He could say, practically without an accent, “Ik ben een Canadeze soldaat. Ik kan uw niet verstaan,” meaning, “I am a Canadian soldier. I cannot understand you.”

Today Groesbeek is the home of the National Liberation Museum and the large Canadian War Cemetery where 2,617 Canadian servicemen are buried.

The Dutch people had been treated very harshly by the Nazi occupiers and when the Canadians arrived in Holland, food was scarce and many people, especially in big cities like Amsterdam, starved to death – many Hollanders starved to death during the harsh winter of 1944-45. It got to the point that, on humanitarian grounds, a cease-fire was arranged to allow food to be brought in, dropped by parachute or trucked in from nearby points under Allied control.

As well, many were freezing because the German occupiers had confiscated all of the coal. Dutch citizens were forced to tear down buildings and use the wood to make fires in an attempt to keep warm.

Dave made a special note that many of the Dutch were hungry, really hungry. In fact, they were so hungry that “they were just like birds looking for food. We were well-fed and they’d pick up anything that we dropped on the ground. That’s how hungry they were. The awful thing about war is I really think the civilians take the worst beating because they had to leave their homes and their homes got ransacked. And I don’t know what happened to those people after the war, how they got started again, if they survived. That’s what it was like in Holland.” The Canadian Armed Forces gave them whatever food they could spare.

It was from situations like this that the Dutch were liberated and, over time, were able to return to a normal life. Most of Holland was liberated by Canadian Armed Forces and the Dutch have never forgotten their liberators. The war cemeteries, to this day, are meticulously kept with school students being assigned to look after individual graves. Each anniversary of the end of the war is celebrated and many now-elderly Canadian soldiers who return to Holland during such celebrations are treated as heroes. This year’s 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II will be remembered by the Dutch with heartfelt thanks to their Canadian liberators.

In early February, the regiment was on the march again – into Germany itself! The Allies launched what they hoped would be the final great offensive to drive the Germans back over the Rhine River and thus to bring the war to an end. The offensive was given the code name “Veritable”. Progress was difficult as mud and flooded ground, sometimes three feet deep, slowed the advance. But advance they did, through the Reichswald forest, onto Kleve and into the Hochwald forest area. At that point the offensive was given a new code name, “Operation Blockbuster.” Allied forces, including Dave’s regiment, now faced hardcore SS troops and the fanatical and suicidal Hitler Jugend (Hitler youth). As well German snipers were a constant thorn in the sides of the Allied forces.

As they moved through one war torn village, a sniper fired at their Bren gun carrier. “The bullet entered a leather pouch just above the radio set in front of me. That pouch was meant to hold Bren gun magazines but was empty. The bullet ricocheted but missed all of us.”

On another occasion, as he was stringing a cable from his radio to an otherwise inaccessible observation point on a steep bank, he heard the burp-burp of a Schmeisser submachine gun. “My dive over the bank was instantly automatic and I lay, unhurt, out of sight of the sniper. He probably thought he had got me. Such individuals were truly suicidal because in their decision to stay behind, alone, they knew their action would be their last, and it was, thanks to our infantry.”

In another town that had almost been reduced to rubble, they came under relentless shelling. From a somewhat protected area, the crew saw an old German lady as she attempted to cross the rubble strewn street and kept falling, over and over, but eventually disappeared from sight. “Did she survive, and if she had, did she ever find the relatives or friends for whom she may have been searching? These were questions triggered in our minds by that pitiful incident. It has always struck me as a strange oversight that there is so much remembrance for veterans on November 11th but scarce mention of the millions of civilians involved in war’s carnage.”

Finally, on May 7, 1945, it was all over. Germany surrendered. On that happy day, Dave and his crew were in Nordenham (near Bremerhaven) in northern Germany. “I had led a charmed life. Snipers had missed me, shrapnel had chopped off whip aerials for the 19 radio set several times, yet I only caught a piece once. It must have been at the end of its flight – slowed by my battle dress and a pigskin money belt worn next to my hide. While it penetrated both, I was only nicked and hardly any blood showed! Once again, this time in thanks, I prayed for my safe deliverance. Somebody had to be thanked and my Anglican upbringing still had influence.”

Dave soon found himself back in Holland as he prepared to be repatriated. Before he left that country he participated in a “mardi gras” organized by Dutch citizens. One of the Armed Forces trucks became a parade float and ‘a good time was had by all’. But as Dave said, “There was still a real shortage of food and people were hungry for what to them was a luxury; white bread and anything else that went with it. Hamburgers were served and scraps carelessly dropped by our well fed comrades were snatched from the ground by hungry citizens.”

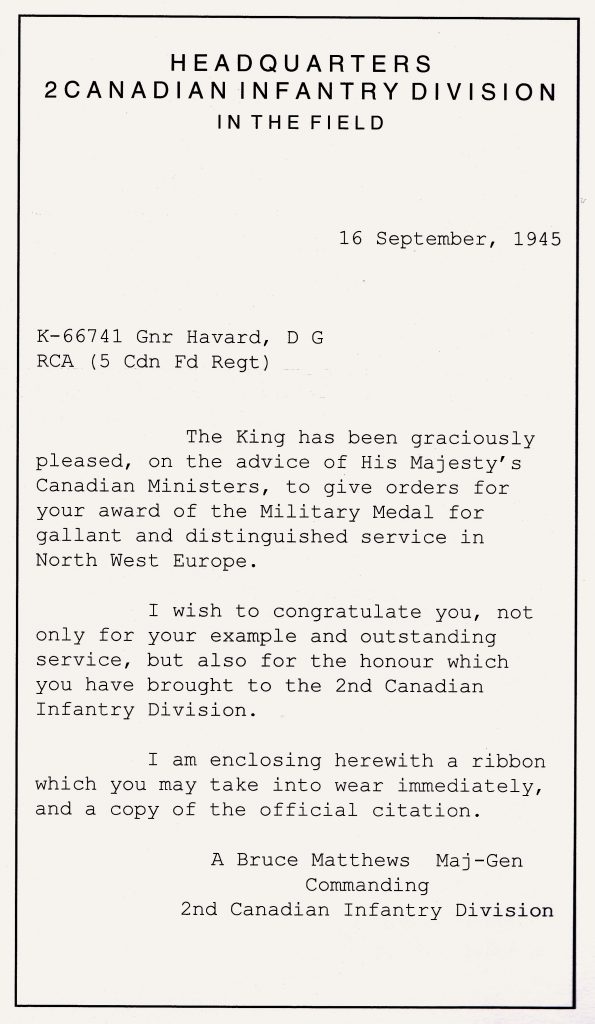

There was one more stop to make before he returned to Canada. That was in London, England. There he attended an investiture at Buckingham Palace and received a Military Medal from King George VI himself! “The moment meant a lot to me. I was so thankful to have tangible proof that I must have done something right.”

Shortly after that, he travelled back to Canada on the Queen Elizabeth troop ship (later converted back to an Ocean Liner). He was officially discharged from the army on January 5, 1946.

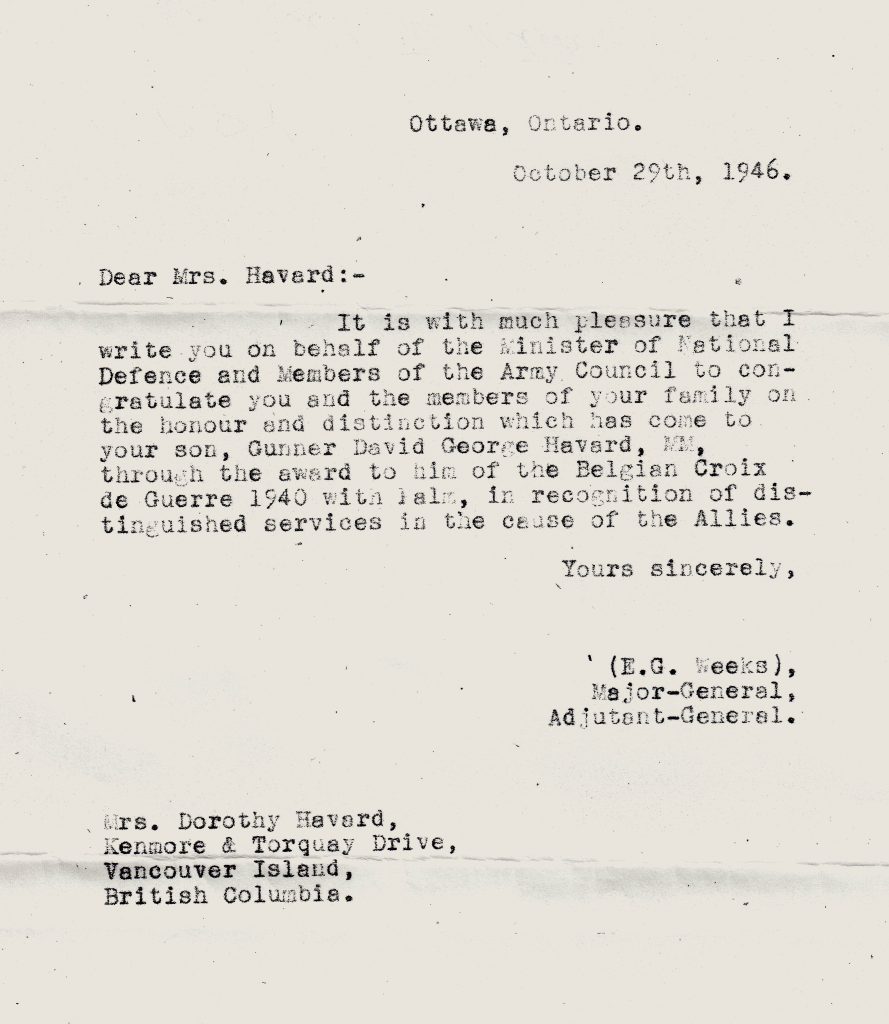

In October 1946, Dave received another surprise as indicated in the letter below to his mother.

Dave always poo-poohed the idea that he did anything special to deserve these medals. Fortunately, there were people who thought otherwise – you don’t get medals like these unless you’ve done something very special! The Military Medal is awarded for “acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire”. Likewise the Croix de Guerre was awarded for “acts of bravery in the face of the enemy”.

In May 1995 Holland celebrated the 50th Anniversary of its liberation from the brutal five-year Nazi occupation of 1940-1945. Most of Holland was liberated by Canadian soldiers. Dave and his wife Rosa returned to Holland to participate in the celebration. While there, Dave received the “Bergen-op-Zoom Liberation 27 October 1944” Commemorative Medal. Bergen-op-Zoom is a city located on the Scheldt Estuary. The medal refers to the role Dave played in the liberation of Bergen-op-Zoom as part of the hard-fought battle of the Scheldt Estuary. It is inscribed with the words, “50 Year Liberation Nederland 1945-1995”.

Thus ended Dave’s wartime service to his country. He had served it well, very well indeed! He returned to civilian life and before long moved to Smithers where he still lives today.

Note from the author: It was been a real pleasure to write this story about Dave Havard’s experiences during World War II. I thank Dave for having shared some of these stories with me over the years and also for having written a book about his early life. It is entitled “Growing up in Victoria (Oak Bay)” and also covers his years in the Canadian Army during the war. Thanks also to his son, Tom, who was very supportive of this story and who kindly lent me the medals Dave received during WWII so that I could photograph them. Much appreciated!

– Harry Kruisselbrink, May 2020.