May 10th – 16th 2021 is Nurses’ Week in Canada, with May 12th internationally recognized as Nurses’ Day. Many dedicated and hardworking nurses have called Smithers home over the decades – from those who served at Smithers’ first hospital in 1921, to those working the front lines during the Covid-19 pandemic today. We have chosen to feature the life story of one nurse who lived here for eighteen years following her retirement, as her story speaks to the opportunities that the field of nursing offered women in past eras, when career options were often quite limited.

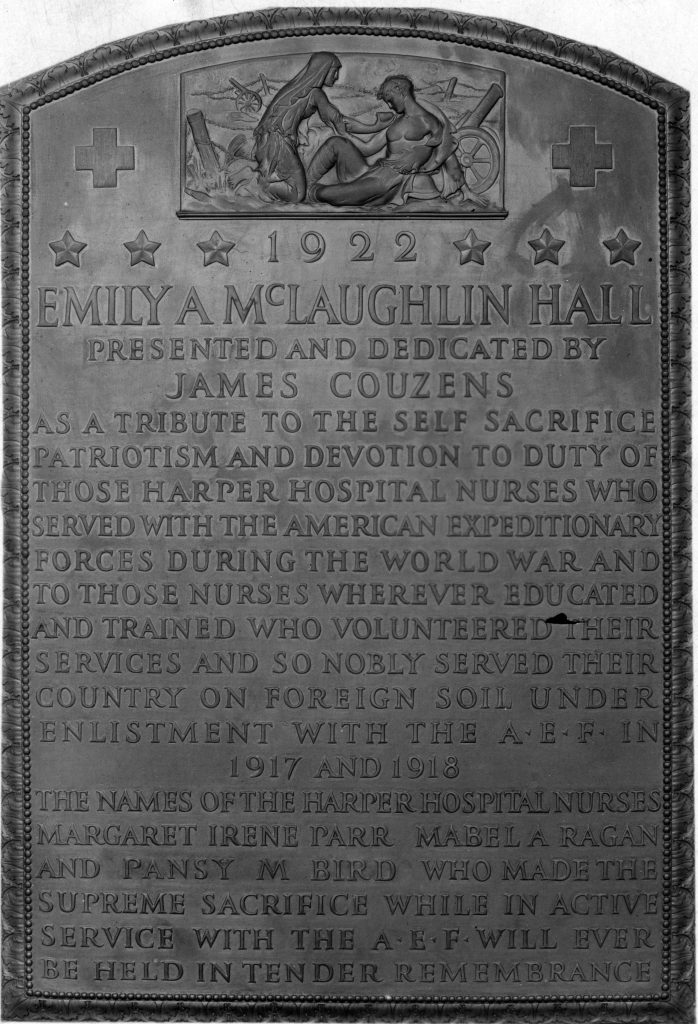

At Block 4, Lot 208 of the Smithers Cemetery, there lies a fairly nondescript, flat headstone. It has sunk into the grass, and could easily escape the glance of a passerby. But the woman who is buried there is in no way nondescript – she was a nurse, a teacher, and a decorated veteran of two wars, with a building named after her in the city of Detroit, Michigan. Her name was Emily Austin McLaughlin.

Early Life

Emily Austin McLaughlin was born on July 12th 1874 in Brooklyn, New York to Charles McLaughlin and Emily Austin. Charles McLaughlin was a school teacher, and is recorded in the 1880 US census as being the principal of a school in Brooklyn.¹ Charles was a Canadian by birth, and through him Emily is a cousin to two other former residents of Smithers buried in the cemetery here, Margaret McLaughlin Dunlop, and her sister Loyola McLaughlin.

According to a May 11th 1880 death record, Emily’s mother, Emily Austin, passed away from consumption, known today as tuberculosis, when Emily was just six years old.² Tuberculosis is not pleasant to live with, or die from. It is possible that watching her mother succumb to this terrible infection influenced the young Emily, and led to her future career interest in helping the sick.

In 1896, Emily graduated from the Farrand Training School for Nurses at the Harper Hospital in Detroit. In 1898, she undertook her first service as an army nurse, working at the Letterman Army Hospital in Presidio, San Francisco during the Spanish-American War. Fought between Spain and America between April 21st and August 13th 1898, the war was largely focused on questions of colonial supremacy and influence in the Caribbean and Pacific regions.

Emily continued to live and work in San Francisco until at least 1900. Sometime between 1900 and 1902 she relocated back to Detroit, presumably working at the Harper Hospital. By 1911 she had become the head of the Farrand school – the same program from which she had graduated from in 1896.

The First World War

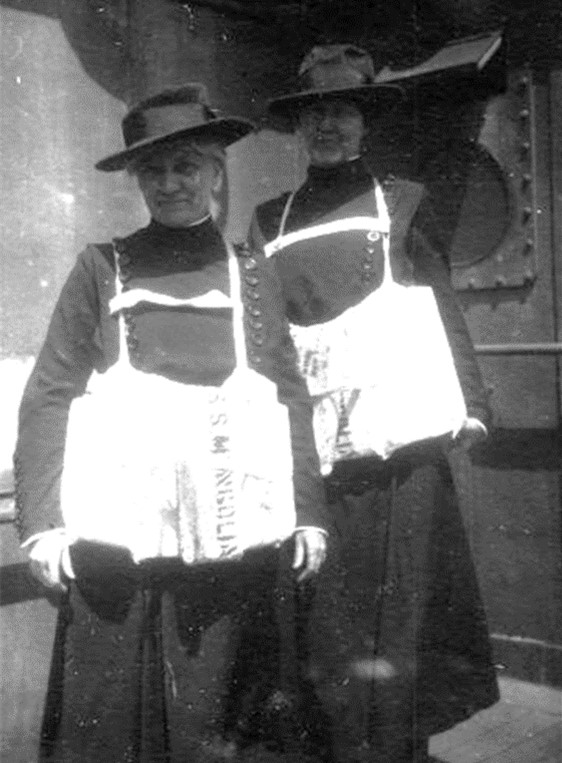

In April of 1917, after nearly three years of neutrality, the United States joined the First World War. By July, hundreds of Americans had been mobilized to join the fight in Europe, including nurses from the Harper Hospital. Sailing from New York to England before moving on to France, the Harper nurses were deployed at the US Army Base Hospital No. 17 in Dijon France. Emily was the chief nurse, responsible for a staff of sixty-five other nurses. The Harper nurses would remain in France until March of 1919.

While in France, Emily and the Harper Hospital nurses witnessed all the terrible injuries and illnesses caused by the war, from patients who were shelled, shot, or gassed, to those suffering from diseases or trauma brought on by living in the trenches. The heroism and dedication of the Harper nurses did not go unnoticed; in 1919, the Detroit Free Press reported that Emily and another nurse, Flora McGregor, were to be decorated by the French for valour in action at Soissons. The Battle of Soissons, fought in July 1918, was waged by the French with British and American assistance, against the German lines. It is considered a major turning point in the war, as after that battle, Germany remained on the defensive until the war ended in November.

Under Emily’s guidance as head nurse, the No. 17 base hospital was one of two army hospitals that received a special commendation in 1919 from the Surgeon General of the United States for work on facial reconstructions and facial operations during the war. Prior to the First World War, facial injuries were the result of a single bullet wound, or a sword cut. But in this war, advancements in weaponry, including shells filled with shrapnel, resulted in truly horrific facial injuries. The advancements in facial surgeries and reconstructions that resulted are often considered the birth of the modern age of plastic surgery, and it appears that Emily was at the forefront of this innovation.

Commendations

On November 13th 1919 Emily was awarded the Royal Red Cross, First Class by the Prince of Wales at a ceremony at the British embassy in Washington, in recognition of her service as chief nurse of the base hospital, and the care of the many British soldiers who were treated there. The Royal Red Cross is a military decoration usually only awarded to citizens of the UK or Commonwealth in recognition for exceptional services in military nursing. It was established in 1883 by Queen Victoria, and was first awarded to Florence Nightingale. The Prince of Wales at that time was Prince Edward, later Edward VIII, who abdicated the throne in 1936 to marry Wallis Simpson.

Retirement and Move to Smithers

Emily retired from nursing in 1927, at the age of 53. In 1945 she moved to Smithers, where, as was previously mentioned, her cousins Margaret Dunlop and Loyola McLaughlin lived. We know from newspaper records that Emily had visited Smithers at least twice previously, in 1922, and in 1942, when she stayed for two months. In Smithers Emily was known (for reasons unknown) as “Aunt Pete”.

Emily appears to have lived a quiet life in Smithers after her retirement, visited regularly by her cousin Margaret’s children. She lived in Smithers for eighteen years, passing away on March 30th 1963 at the age of 88.

Unconventional, and Remarkable

Emily’s life was in many ways unconventional for a woman of her era, but stands as a testament to the roles that that women played in the armed forces, and the development of medical practice. While we cannot know for sure how or why she made certain choices, and many women of her era did have both a traditional marriages and family and a career, it is notable that Emily herself never appears to have married; this potentially deliberate choice allowed her to focus on her nursing career, where she influenced the lives of hundreds of others, both as a teacher, and as nurse and healer.

Enjoy the story? Join the BV Museum for its Cemetery Walk, held annually in October.

Footnotes:

1. The family name is sometimes spelled “McLoughlin”, including in these 1880 census records. The “McLaughlin” spelling is used here for consistency with the majority of records available that pertain to Emily, including Detroit Free Press newspaper articles, and the Harper Hospital collection at Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

2. The death record for the Emily A. McLaughlin who died in New York on May 11th 1880 records that she was unmarried. However, based on all other evidence, it appears likely that this is indeed the death record for Emily’s mother – the chances of there being another Emily A. McLaughlin of the same age in the same area seems highly unlikely. Also, the 1880 census page that records Charles, Frank, and six year old Emily as the only members of the household was dated to June, therefore the information would have been recorded after the senior Emily’s death. It is possible that her marriage status was recorded as single in error, or that she and Charles had separated.

Selected references:

Many thanks to Elizabeth Clemens, Audiovisual Archivist at the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University for sharing the many wonderful photos of Emily that are archived as part of the Harper Hospital collection. See http://as.reuther.wayne.edu/repositories/2/resources/1463/collection_organization for the Harper Hospital collection.

Detroit Free Press, various years. Accessed through newspapers.com.

“Miss McLaughlin Had Distinguished Career”. Smithers Interior News, April 3 1963. Accessed through newspapers.com.

US Army Centre of Military History: Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps. https://history.army.mil/html/books/085/85-1/CMH_Pub_85-1.pdf, accessed October 2020.