Fifty years ago, on June 30th 1971, the following headline could be found over a small article buried on page 13 of the Smithers Interior News: “Mammoth found in mining dig“.

Despite not being considered front page news, the discovery of a mammoth skeleton at the Noranda Bell Mine site on the Newman Peninsula of Babine Lake remains a significant paleontological discovery. As outlined in a 2016 Northword Magazine article by author Jane Stevenson, the Bell Mine mammoth, better known as the Babine Lake mammoth, was hurriedly excavated over the course of two days by Canadian geologist Dr. Howard Tipper. Working through wet conditions, largely with a bulldozer, Tipper and his team excavated 12 large crates worth of material, including tusks, vertebrae, leg bones, ribs, and geological samples. This material was sent to the National Museum of Natural Sciences (now the Canadian Museum of Nature), where it was catalogued into their permanent collection as CMNFV 17914. The bones were identified as those of a Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) by museum staff member Richard Harington, who concluded that “the Babine Lake mammoth would have had an estimated height at the shoulder of 10 feet, 10 inches or perhaps 11 feet, four inches in the flesh”. A 1974 report by Harington and Tipper for the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences stated that radiocarbon analysis from an anterior rib fragment dated the mammoth to approximately 34,000 (± 690) years before present.

In 2002 two bone fragements of the Babine Lake Mammoth were donated to the Bulkley Valley Museum by the wife of a crew member who had worked at the Bell Mine site in the 1970s. It is believed that several pieces of the mammoth, including its teeth (which usually preserve well, but were not found at the site by Tipper), were removed by workers prior to the official excavations in 1971. As a result, several pieces of this mammoth are likely held in private collections. The fragments donated to the Bulkley Valley Museum are some of the few known pieces of the Babine Lake mammoth that still reside in British Columbia.

In 2018 the BV Museum was contacted by PhD candidate Laura Termes of the Department of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University. Laura is one of the researchers working on the BC Megafauna Project, which aims to examine and document the ice age mammal remains recovered from all over BC currently housed in both museum and private collections. Laura proposed sampling the BV Museum’s mammoth bone fragments to see what could be learned through modern radiocarbon dating (as the last dating was done four decades ago) and isotopic analysis techniques.

We originally sent Laura a small sample of material that was flaking off of fragment 2009.23.1. Unfortunately, this 7 gram sample did not contain enough collagen (a structural protein found in the connective tissues of bone, muscle, tendons, and ligaments) for radiocarbon dating or isotopic analysis.

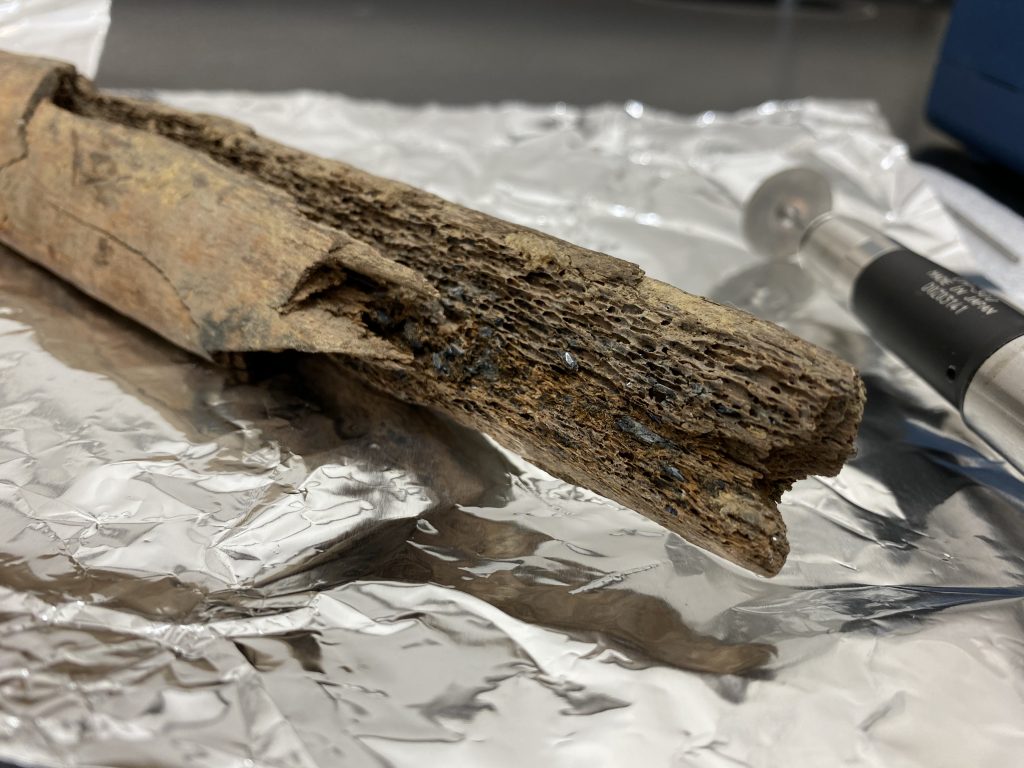

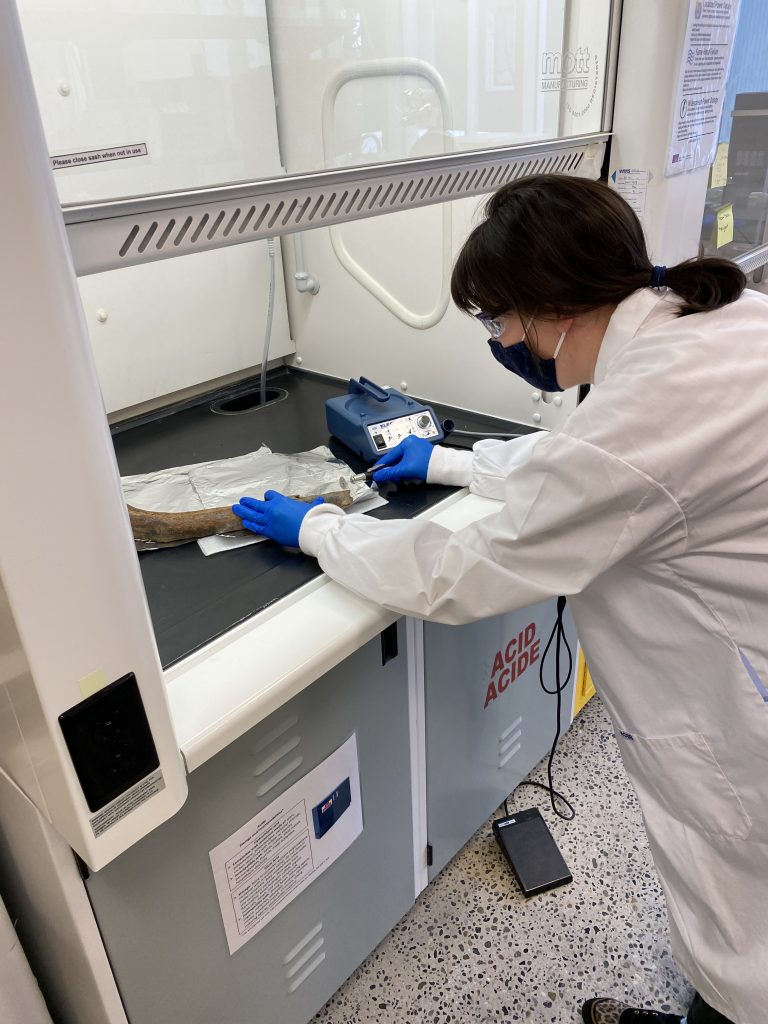

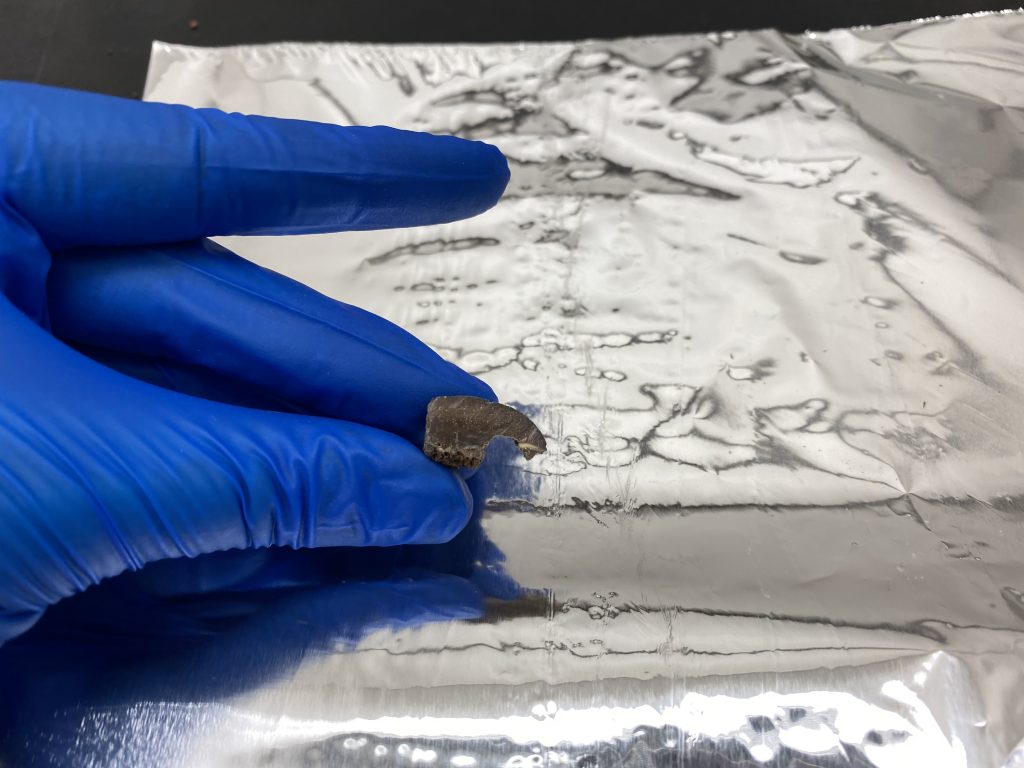

After striking out with a sample that had become disassociated due to natural degradation, we moved on to the more stable mammoth rib bone, 2009.23.2. While Laura had originally hoped to visit Smithers to collect the sample in person last summer, COVID-19 restrictions put that plan on hold. In order to remove a sample in the most minimally invasive way possible, we shipped the entire rib bone to SFU in January 2021 so that Laura could use specialized tools to extract the sample she needed to complete the tests.

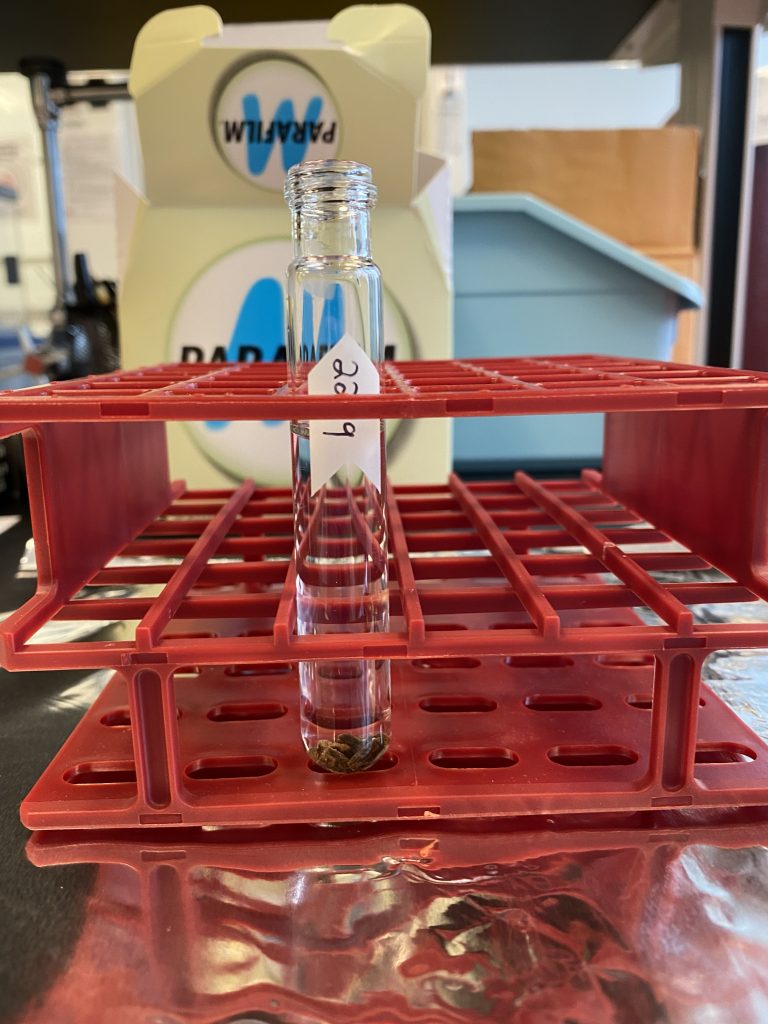

Laura shared the following photos that detail the collagen extraction process:

Once collagen sampling has been successfully completed, Laura will proceed with running further tests on the sample. We look forward to sharing the results with you soon!

Sources consulted / further reading:

“Mammoth found in mining dig”. Interior News, June 30th 1971.

Stevenson, Jane. “A mammoth discovery: decades later, fossils still shrouded in mystery”, Northword Magazine, August 1st 2016. http://northword.ca/features/a-mammoth-discovery-decades-later-fossils-still-shrouded-in-mystery, accessed January 18th 2021.

Harington, C.R., H.W. Tipper and R.J. Mott. “Mammoth from Babine Lake, British Columbia”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences (Volume 11:2, February 1974). https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/e74-025, accessed January 18 2021.

“Mammoth donation unearths archaeological cover up in Granisle”. Interior News, July 17th 2002.

British Columbia Megafauna Project at Simon Fraser University. https://www.sfu.ca/megafauna.html, accessed January 18th 2021.