This blog post marks the close of Asian Heritage Month, which celebrates and commemorates Canadians of Asian descent. We have chosen to focus on the Smithers Bakery, which was run by Mah Yoke Tong from 1919 until his death in 1955. His great-nephew Mah Wing Shek then took over the business until its sale in 1965. This family-run bakery was a popular shopping spot for Smithers residents and, as noted in Tong’s Interior News obituary, was one of the oldest established businesses in town.

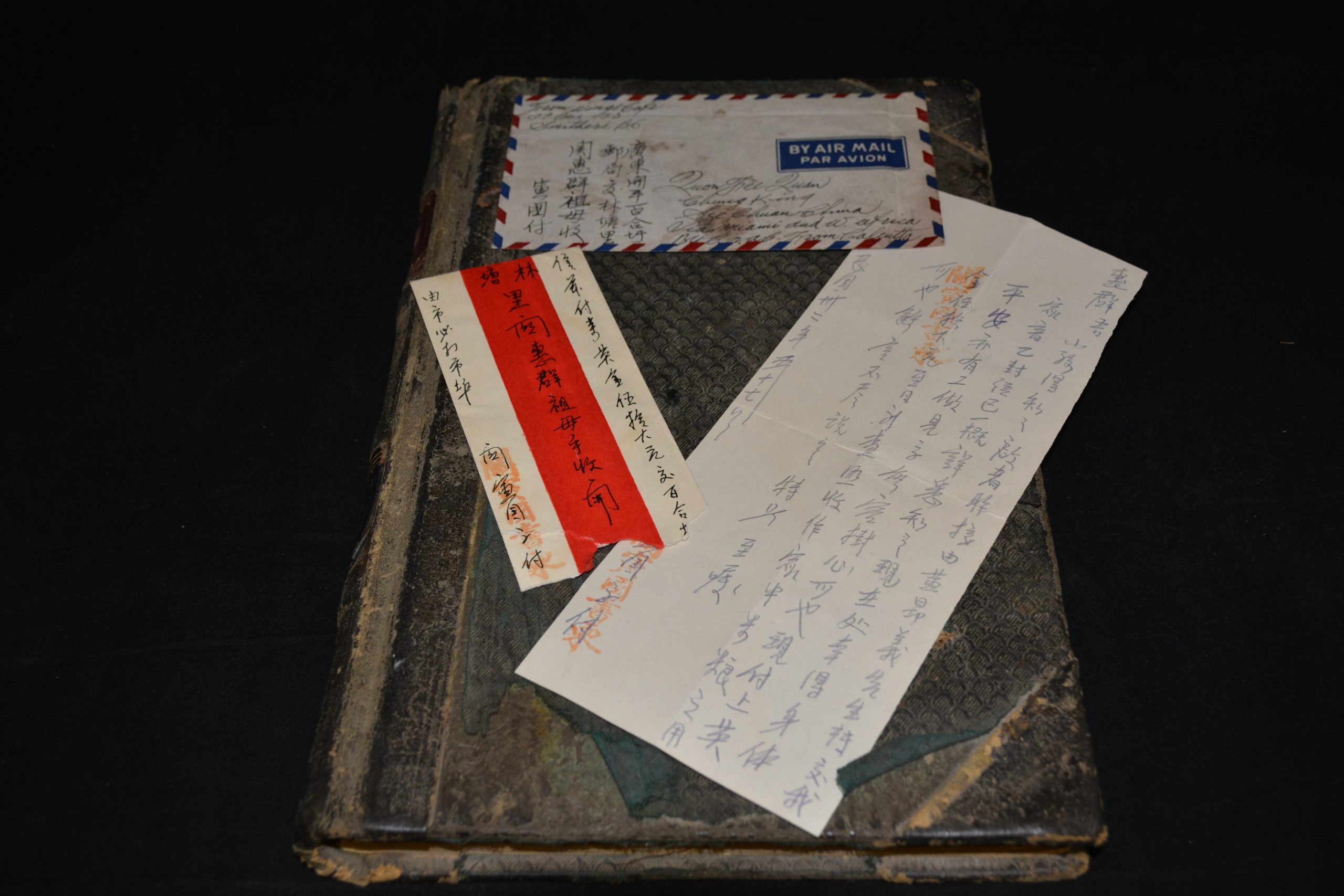

Artifacts in our collection related to the Smithers Bakery include a pan, bread wrappers, and tokens entitling the holder to one free loaf. We also have a ledger recording Bakery sales from the 1930s to the 1950s. Perhaps the most meaningful item is a letter dated Year 3257 (1935) from Tong to his grandmother, Quon Fee Quan, in China. In it he wishes her and the rest of the family peace and happiness, and encloses $50 for them to buy food. This was a considerable amount of money, especially during the Great Depression. More than any of the other artifacts, this short missive provides a glimpse into Mah Yoke Tong as a person.

Born on December 14th 1870, in Bai Sha Tong village, Taishan County, Guangdong, China, Tong immigrated to Canada as a young man in 1892. He first worked at Ladysmith and Nanaimo on Vancouver Island. In the early 1900s, he journeyed up the Skeena River to the Bulkley Valley where he joined a business partnership with a fellow Chinese immigrant in Hazelton. After living for a time in Aldermere and Telkwa, he finally arrived in Smithers in the mid-to-late 1910s, possibly as early as 1915. At this time, the Smithers Bakery was known as City Bakery & Confectionary and owned by Stanley C. Jones. Mah Yoke Tong purchased it in 1919. The building stood at the intersection of Main Street and First Avenue, where Eckland’s Denture Clinic is located today. Tong’s nephew, Mah Chong (father of Mah Wing Shek), ran a laundry business in town, and the two men appear on the 1921 Canadian Census along with 33 other Chinese residents of Smithers.

Emigrating from China to Canada at this time was not easy. The racist Head Tax policy, first enacted by the Federal Government in 1885, aimed to limit the Chinese-Canadian population by charging every Chinese immigrant a fee. This reached a staggering maximum of $500 per person in 1903. Such punitive and exclusionary measures were not applied to newcomers of any other ethnicity. Mah Yoke Tong had personal experience with this policy. In addition to paying his own head tax, he helped sponsor his great-nephew Mah Wing Shek (‘Little Wing’), who arrived in 1922. This was only one year before the Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese immigration to Canada almost entirely – it would not be repealed until 1947. Furthermore, Tong’s obituary indicates that he had a wife and children in China who were never able to join him. One of the most tragic effects of the Canadian Government’s discrimination towards Chinese immigrants was the break-up of families, in some cases forever.

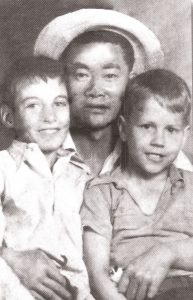

Mah Yoke Tong nonetheless carved out a place for himself in Smithers, gaining a reputation for generosity and kindness. He frequently gave away candy and baked treats to local children, and supported charitable endeavours such as the Bulkley Valley District Hospital. In particular, his Bakery was remembered by many Witsuwit’en elders as providing quality, non-discriminatory service to Indigenous patrons – something sorely lacking in many other Smithers businesses. Fellow Chinese pioneer Lee ‘Irish’ Tong (no relation) was also known for serving First Nations customers in his O.K. Café when other restaurants would not. (More info on the relationships between Chinese settlers and the Witsuwit’en can be found in Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relationships in Smithers, British Columbia by Tyler McCreary). After Mah Yoke Tong’s death, his fellow Main Street business owners paid him tribute by closing their doors from 2 to 4 p.m. in the afternoon.

The stories of Asian-Canadians such as Mah Yoke Tong and his relatives are an important part of our country’s past, present, and future. They prove that diversity has a long and proud history within Canada, while also standing as a reminder of the racism and discrimination which people of colour endured (and still do). This article provides just a glimpse into the history of Asian-Canadians in the Bulkley Valley. It is based off information from the exhibit Asian Canadians of Smithers: 1913-1953, which was held by the Bulkley Valley Museum in 2017.

If you would like to learn more about this topic, the Museum is always willing to receive research requests by phone (250-847-5322) or e-mail (info@bvmuseum.org), and our collections are searchable online at www.search.bvmuseum.org.