Burning Questions

While browsing the Museum’s photo collection last summer, we came across a mystery: four photos showing the aftermath of a major fire. They had no associated information: no date, no donor, and no location aside from a note saying “Smithers BC”.

There are many unidentified photos in the Museum’s collection. However, we found these images compelling because many of the photos in our collection are posed or planned – workers hamming it up in front of a train car, a townscape shot of Smithers from an 1952 aerial survey, an idyllic shot of a person standing on a dock at Lake Kathlyn. In comparison, these mystery photos feel more raw, the photographer acted as a journalist here. Early 20th century camera technology – with its more cumbersome equipment, longer exposure times, and its reliance on physical film – limited journalistic photography, which makes this instance of it all the more special.

The subject matter of the photos make them even more interesting. Photos of fires – especially early 20th century fires – in our collection are rare. Of the over 6800 photographs in our Archives, only 20 or so document fires. Of these, several document bush fires or fires in other communities. This lack of photos would seem to imply that Smithers was relatively fire free, but in reality the town has a long history with this elemental force.

Smithers’ Fire History

One such example can be found in local history book Swamp to Village. The book notes that shortly after the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway founded Smithers in 1913, a fire assisted its growth at the expense of the neighbouring (and much more established) Telkwa. On April 13, 1914 – six days after the first train passed through Smithers – a major fire tore through Telkwa, destroying multiple businesses. Several of these business owners decided to rebuild in Smithers instead of Telkwa, kickstarting the new community. [1]

The sounding of Smithers’ fire hall siren every day except Sunday – a prominent (and sometimes alarming) Smithers tradition – also has its origin in fire. This tradition has existed since at least 1956, when a siren was installed in the community’s fire hall at its old location on Fourth Avenue north of Main Street. [2] However, the tradition may have begun earlier. An Interior News article in 1949 notes the following:

“As a result of the failure of the village fire siren on the occasion of the recent fire, arrangements have been made between the Telephone office and the council to blow the siren every day except Sunday at 12 o’clock noon. The siren had formerly been sounded only on Saturdays, but apparently this is not often enough to ensure that it is in good working order as was shown when it failed to work after a short blast during the Smithers Garage fire.

This new policy caused a flurry of excitement on Monday of this week when few were aware of the change. To make matters worse a short developed in the wiring and the siren wouldn’t shut off until the hand switch was pulled. Incidentally the siren won’t be sounded on Sundays.” [3]

Other notable local fires include the Smithers Confectionary fires of 1954 and 1960, the Hudson Hotel fire of 1973, the Pacific Inland Resources fire of 1993, and the fire that destroyed the 80 year old Bulkley Hotel (also in 1993). For a good historical background of Smithers’ fires, see Chapter 6 (pages 97-104) “Smithers Rises From the Ashes” in Chronicles of Smithers – Our 100th Anniversary by the Bulkley Valley Genealogical Society.

But which of the many fires from Smithers’ history do these four mystery photos document?

Chasing Smoke: Identifying Historical Photos

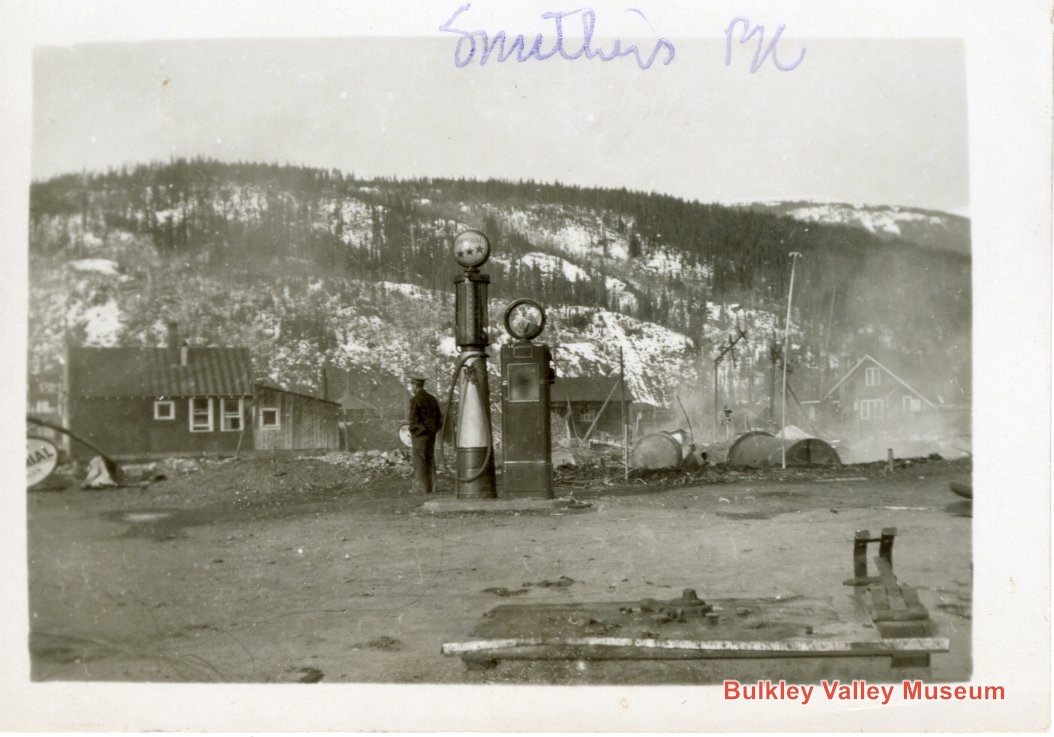

Our first step was to establish the general location of the fire. Residents of Smithers will likely recognize the rocky outcrop in the background of P5552; this is a view of the steep hill rising beyond the railway tracks to the west of town. [4] The size of this feature suggests that the photo was taken closer to the west side of town. The presence of snow on the hillside but absence of snow in town suggests that this fire occurred during a shoulder season – either fall or spring. P5552 also provides another clue: the prominent gas pump in the foreground indicates a gas station or some other vehicle related building once stood here.

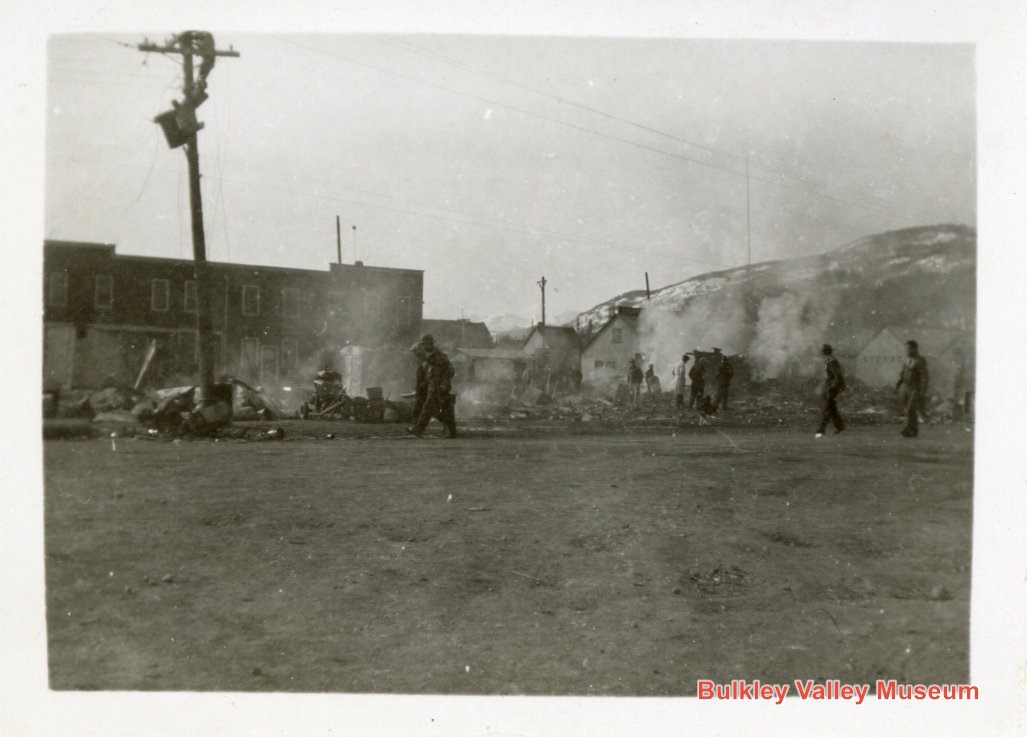

In P5554, we found another crucial clue on the sign above the building’s entrance. It appears to say “Sandys”. According to Chronicles of Smithers, Sandy Gazeley operated a barber shop on the north side of Main Street between Broadway and Alfred Avenues from the 1930s to the 1950s. [5] Furthermore, one can just barely make out a barber pole jutting from the right side of the building. Importantly, the distant background does not show the same geographical features as in P5552: it’s more distant and lower on the horizon. This suggests that this photo is looking east in the direction of the Babine Mountain Range (though farther to the north as none of the mountains themselves – such as Mount Cronin – are visible). With these two photos we established a rough location for at least part of the fire: the northeast corner of Broadway Avenue and Main Street – where Bovill Square now stands.

P5553 hinted to us that the fire may not have been confined to the north side of Main Street. This theory came from the object found in the center of this picture and which is also found in the right foreground of P5554. P5553 then looks up Main Street to the east, towards the Central Park Building. Note the right side of the picture and the lack of buildings in the background; we wondered, did the fire damage the southern side of Main Street as well?

In P5555 we can see another ridge in the far background. The ridge appears too close to be the Babine Mountains, so the photo must be facing to the west like P5552. The more gradual relief means we are not looking at Grad Rock, as we were in P5552, but rather to the south of Grad Rock – if we were looking to the north we would see the profile of Hudson Bay Mountain.

The most important clue though is the building in the left of this image. At the time, this building housed the McRae Hotel. If it looks familiar to modern day ‘Smithereens’, it is because the building still stands on the southwestern side of Broadway Avenue: it is the building that houses Fitness Northwest today. The closeness of the building to the ruins added further credibility to the theory we developed about P5553: that the fire damaged both the northwest and southwest corners of Main Street and Broadway Avenue.

The presence of the McRae Hotel on the edge of the fire helped us narrow our search down to the years 1944 and 1945. Both years, large fires erupted on the western end of Main Street. In both instances, the flames damaged the McRae Hotel but ultimately spared the building from destruction. We therefore turned our attention to these two fires – arguably the most destructive in Smithers’ history.

The Infernos of 1944 and 1945

In May 10, 1944, the Interior News documented the first of these fires:

“The fire broke out shortly after 9 p.m. in the premises of the Blue Goose Cafe when a gas burning coffee maker caught fire. … By the time Forestry equipment arrived on the scene the fire had spread to Anger’s Tailor Shop and residence upstairs, the flames soon gathering such headway that all the available facilities were unable to cope with the situation The [Noel] Drygoods and [F]urniture [S]tore was the next to fall victim to the flames and efforts were made towards saving as much of the stock as possible. The Day Bakery, in the Newbery Building, finally caught fire, adding to the intensity of the flames and heat. The former Gray Jewelry Store, recently vacant, was the last to catch.

Additional fire fighting equipment which arrived from the C.N.R. and the Smithers Airport in the meantime, was directed toward preventing the spread of the flames to other buildings across Main Street, and the McRae Hotel, a workshop and residences on Broadway avenue.” [6]

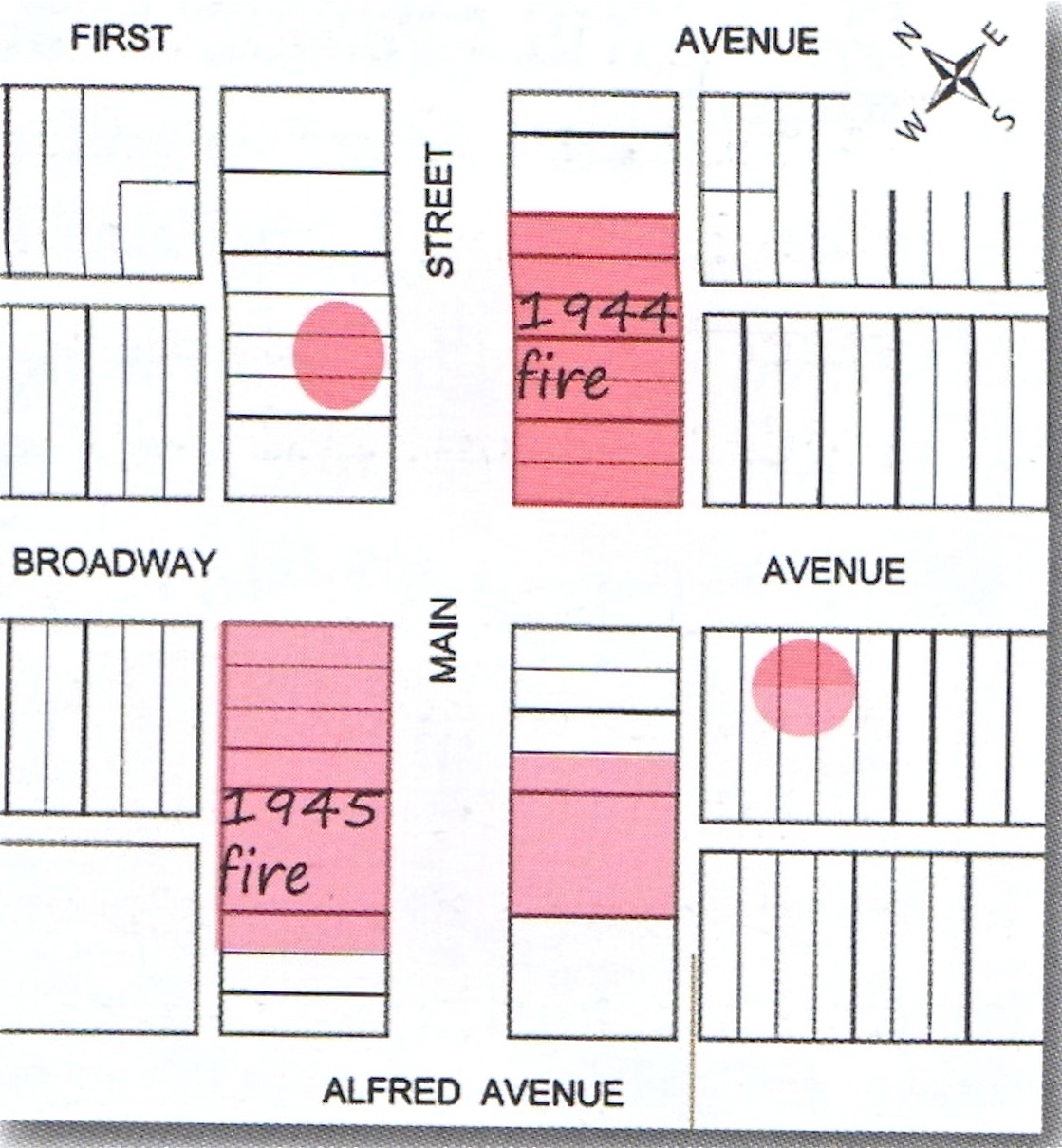

A large fire? Check. During spring? Check. Near the McRae Hotel? Check. However, there is no mention of a vehicle-based business (as suggested by the gas pump seen in P5552) nor a sense that the fire burned buildings on both sides of main street (as suggested by P5553). Chronicles confirmed our suspicions with a helpful map of the 1944 and 1945 fires. This proved essential to our research as we could see that the 1944 fire began midway down the southern side of Main Street between First Avenue and Broadway. Those locations did not match up with our theories; on the other hand, the 1945 fire now appeared to be a promising candidate.

The Interior News documented the 1945 fire on April 5 of that year:

“The fire was discovered shortly before 8 o’clock … and originated in the vacant lot off Main Street owned by [illegible] and known as the Henry [illegible]. It had not been occupied for some time. … the Kennedy Building offered [illegible] fuel for the flames and in … a few minutes this building [illegible]. Wall’s Garage on the corner opposite the Bank and Stewart’s were soon victims of the flames. … While the wind fanned flames towards the south the heat from the Henry Building had set afire the adjoining building owned by Danny Small and occupied by the City [Transfer]. Only quick action … saved the [contents] of the building, and fortunately the Canadian Legion Club, was spared.

… Fire fighting equipment was hampered by the rapid spread and size of the fire, and when it was finally organized properly there was no water. Flames were leaping into the street before an adequate source of water was obtained, but in the meantime the Air Force equipment was used to good advantage in saving Gazeley’s home and barber shop. Lack of sufficient water to supply the available nozzles probably resulted in the spread of the fire to the opposite side of Main Street and soon the Elliott Shoe Store and Wimpy’s Cafe … were added to the conflagration. The Day Bakery adjoining Elliott’s was also doomed and every effort was concentrated on saving the McRae Hotel … Village and Air Force equipment poured streams of water on two sheds near the hotel and on the building itself for the better part of an hour, and although it seemed sure to go at one time but the flames were finally checked.” [7]

All signs pointed to this fire being the subject of our mystery photos. Wall’s Garage and Taxi, one of the first victims of the fire, is a vehicle-based business that was located on the northwestern corner of Main Street and Broadway. This is the ruined gas pump in the foreground of P5552. The article details how the Air Force’s firefighting equipment saved Gazeley’s barber shop and P5554 shows just how close the fire got to the building. In the right half of the same picture we can see the ruins of the Stewart’s Cafe and the Kennedy Building. P5555 shows the results of the fire as it jumped across Main Street to the buildings on the southwestern block of Broadway. In the foreground we can see the smoking ruins of the Elliot’s Shoe Store and the Bowland Building which housed Wimpy’s Cafe, and the Day Bakery. [8] In the background, we can see the McRae building damaged but still standing. (Jump to mystery photos.)

To confirm our hypothesis we sent the photos and our theory to Harry Kruisselbrink, a local resident interested in Smithers history. He agreed that it was likely the 1945 fire. He pointed out that in P5554 you can make out the Pioneer Block building on the right hand side of the photo. The presence of this building, on the northeast corner of Broadway and Main, further supported our theories. At the time of the picture the Pioneer Building would have housed the Hanson Lumber Company and the Royal Bank of Canada. Today it is the home of the Sausage Factory and a heritage building on the BV Museum’s Culture Crawl – a historical walking tour of Smithers oldest buildings.

Further confirmation of our theory came last week, when we discovered two more photos of the same fire, adding other perspectives of the damage.

![[alt text]](https://bvmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/p1242-1.jpg)

![[alt text]](https://bvmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/p1217.jpg)

The photographer of P1242 and P1217 took these photos some time after the fire. In P1242 the wooden sidewalk is being rebuilt, and in both pictures the smoke that dominates the previous photos has disappeared. The clarity of these photos confirms details we could only guess at in other photos: the Pioneer Building is in the center of P1242 and we can see the word ‘hotel’ on two different signs in P1217 confirming the identity of the McRae Hotel.

Why Does This Matter?

While major structure fires still occur in Smithers – such as the devastating August 2013 fire that destroyed several buildings on the western end of Main Street – the 1944 and 1945 fires served as a catalyst for improving fire fighting services. One major development was the procurement of a reliable water source for fire fighting. Citizens and the local government did not want a repeat of the 1945 fire where a “lack of sufficient water to supply the available nozzles probably resulted in the spread of the fire to the opposite side of Main Street”.[9] In a 1947 referendum citizens voted to install water lines. The municipal government installed these water lines in 1948 and fire hydrants in 1949. Prior to these improvements, fire fighters procured water on an ad hoc basis, often from the large ditch running down Main Street. [10]

While articles from the Interior News helped us understand the facts of the 1945 fire, these images help us understand how the fire must have felt to the residents of Smithers. We can imagine how this must have traumatized citizens of the town. In this way, these images help historians and teachers engage their audiences in a way that words alone cannot. Already one of these images is being used in a new local history book, Shared Histories by Tyler McCreary.

Other benefits are tertiary to the actual content of the photo. The research process into these images lead us to ‘discover’ that the Fitness Northwest Building is a heritage building. While it has undergone significant renovations since its construction in 1929, this building has stood for 89 years. In a town with only 105 years of history, this is significant. As a result, we may include the building in future BV Museum Culture Crawls.

The research process also serves as inspiration for staff and other local history buffs to try their hand at solving other museum mysteries. The BV Museum has a number of unidentified photos of both people and places and we encourage anyone interested in tackling these mysteries to search our collections online database for the words ‘unidentified‘ or ‘unknown’.

If you would like to learn more about the history of fire fighting, visit the fire hall to see the new panels that have been created in collaboration between the BV Museum and the Smithers Fire Department, consult the chapter on local fires in Chronicles of Smithers (available at the Smithers Public Library), or pick up a copy of Shared Histories – for sale at the Speedee Interior Stationary, Mountain Eagle Book, and the BV Museum.

A big thanks to Harry Kruisselbrink for proof-reading and fact-checking this article.

Endnotes

[1] Lynn Shervill, Smithers – From Swamp to Village, p. 18.

[2] Bulkley Valley Genealogical Society, Chronicles of Smithers, p. 15.

[3] Chronicles of Smithers, p. 74, 204. In an e-mail correspondence with museum staff, Harry Kruisselbrink, a long-time Smithereen, remembered the noon alarm when his family arrived in 1952. He also noted that around this time Canadian National Railways sounded a whistle multiple times a day. He states that, “The first blast was at 7:00 AM (to tell railroaders to get up), the next at 7:45 AM (to tell them to be on their way to work) and another at 8:00 AM (to be at work). They also blew the whistle at noon (lunch time), at 12:45 PM (lunch is over – get back to work) at 1:00 PM (be at work) and at 5:00 PM (quitting time).” Like the noon time siren, this routine was also put on hold during Sundays.

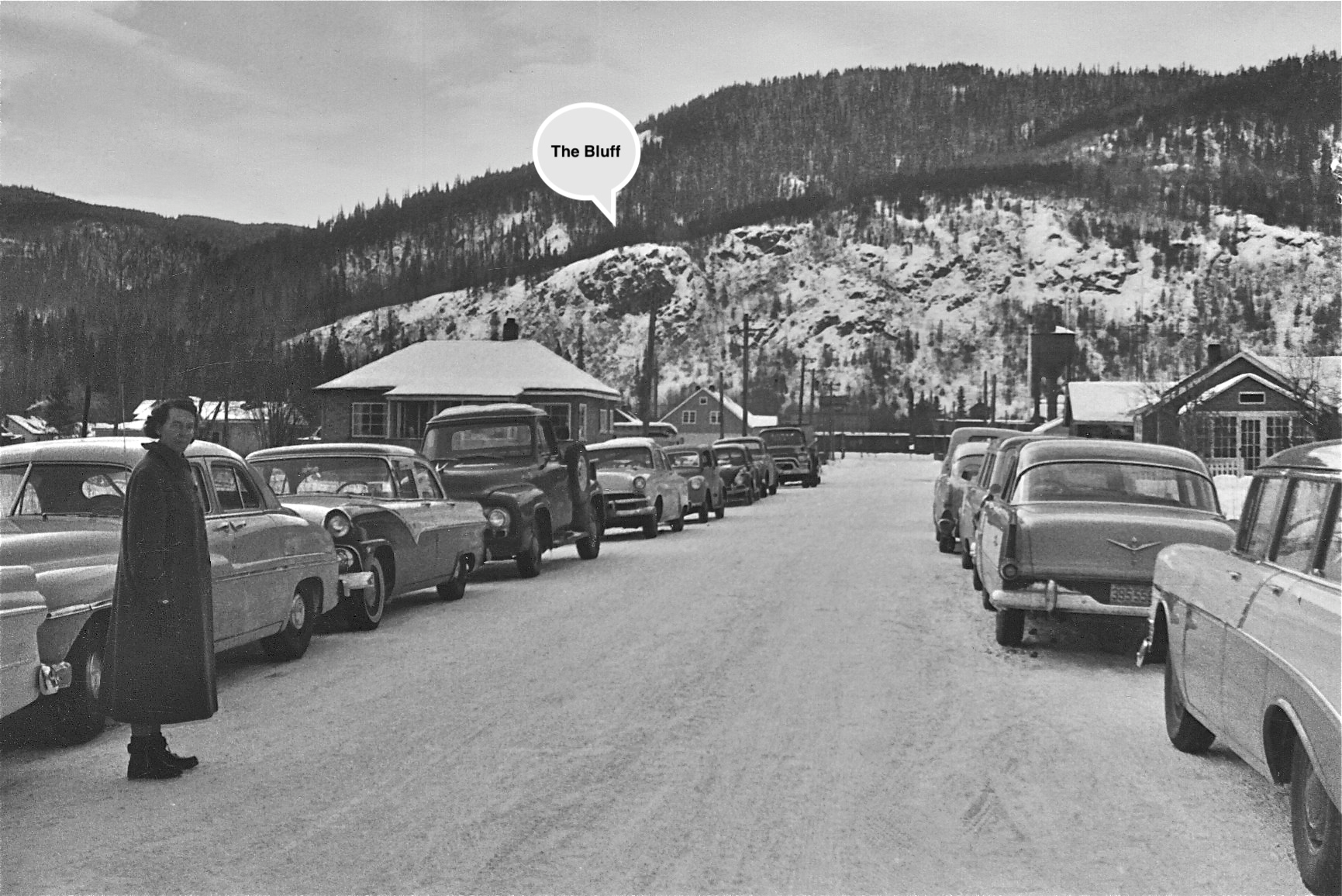

[4] What to call this steep hill of exposed rock is an interesting question. Some local would refer to this as part of ‘the Bluff’. However, Harry points out that the Bluff – an area densely packed with multi-use trails and a popular site for local mountain biking – could also more specifically refer to the hillside slightly southeast of the area in P5552.

Another local landmark, ‘Grad Rock’, lies just outside the frame of P5552 on the left. The name Grad Rock is specific to an exposed cliff where local students sometimes informally celebrate high school graduation – at times leaving graffiti. As an interesting aside, Harry Kruisselbrink noted in an e-mail with Museum staff that “the term ‘Grad Rock’ came into existence only after the CNR [Canadian National Railway] blasted ‘The Bluff’ to Smithereens (no pun intended) for [track] ballast in the early 1970s. That blasting provided easy access to the area and the open surface for the grads to put their names on the rock.” Harry enclosed the photo below with an annotation showing the specific section of rock in question prior to its blasting.

This aside highlights the fuzzy boundaries of the Bluff. At its most specific, the term can mean the main hub of mountain bike trails and the area that immediately surrounding it. At its most expansive, the term can refer to the entire hillside which extends northwest out towards Zobnick Road. (Source: Peter Krause of McBike and Sport.)

[5] Chronicles of Smithers, p. 74.

[6] Interior News, “Worst Fire in History of Town Brings Heavy Loss”, May 10, 1944.

[7] Interior News, “Smithers Suffers Heavy Losses by Fire Monday”, April 5, 1945.

[8] Interior News, “Estimate Fire Loss at Well Over $100,000”, April 5, 1945.

[9] Interior News, “Smithers Suffers Heavy Losses by Fire Monday”, 1945. Shame may also have motivated citizens to make Smithers more fire safe. Two weeks after the fire, the Provincial Fire Marshall’s assistant “declared at a meeting with the Village Commissioners … that conditions here were the worst of any village of comparable size” due “residents’ carelessness and the untidy state of back lanes”. Interior News, “Fire Inspector Says Conditions Disgrace”, April 19, 1945.

[10] For an up-to-date overview of the history of fire fighting and general infrastructure development see, Tyler McCreary, Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973, p. 153 – 175. Disclaimer: The BV Museum and its staff assisted with research for Shared Histories.